Two Who Defied the Impossible

Paul Kronenberg has always been a man of action, with volunteer experience in India and Southeast Asia. He didn’t just believe in ideas — he believed in their execution — something he saw as central to the meaning of volunteer work.

Tibet and the Limits of the Possible

Sabriye and Paul begin creating something that has never existed — not just in Lhasa but anywhere in Tibet: a school for blind and visually impaired children. A real school, one where students can not only gain knowledge but also learn to believe in themselves and their own abilities. To many, this intention of Sabriye and Paul seems almost insane, even though most people acknowledge that blind children have the right to a full life.

How do you start a school — how do you attract teachers and convince parents to send their children to such an unusual place when all you have is an idea and nothing more? On the one hand, it seems incredibly difficult, almost impossible. But on the other hand, a deep conviction that you’re doing the right thing also matters. Fully aware of how hard it would be to secure funding — and, even more importantly, to overcome the deep-rooted superstitions surrounding blind children in Tibetan culture — Paul and Sabriye begin their work.

Step by step, overcoming both big and small obstacles and convincing others of the need for such a school in Tibet, they begin building their school. And not just a school, they embark on an even more ambitious project: developing the first-ever Tibetan Braille script.

Braille Without Borders

It’s not uncommon for an idea that initially seems crazy to come to life, firstly, because the creators aren’t afraid to start small. Secondly, sometimes it’s precisely the uniqueness of the idea that attracts both those who can fund it and those who doubt its chances of success.

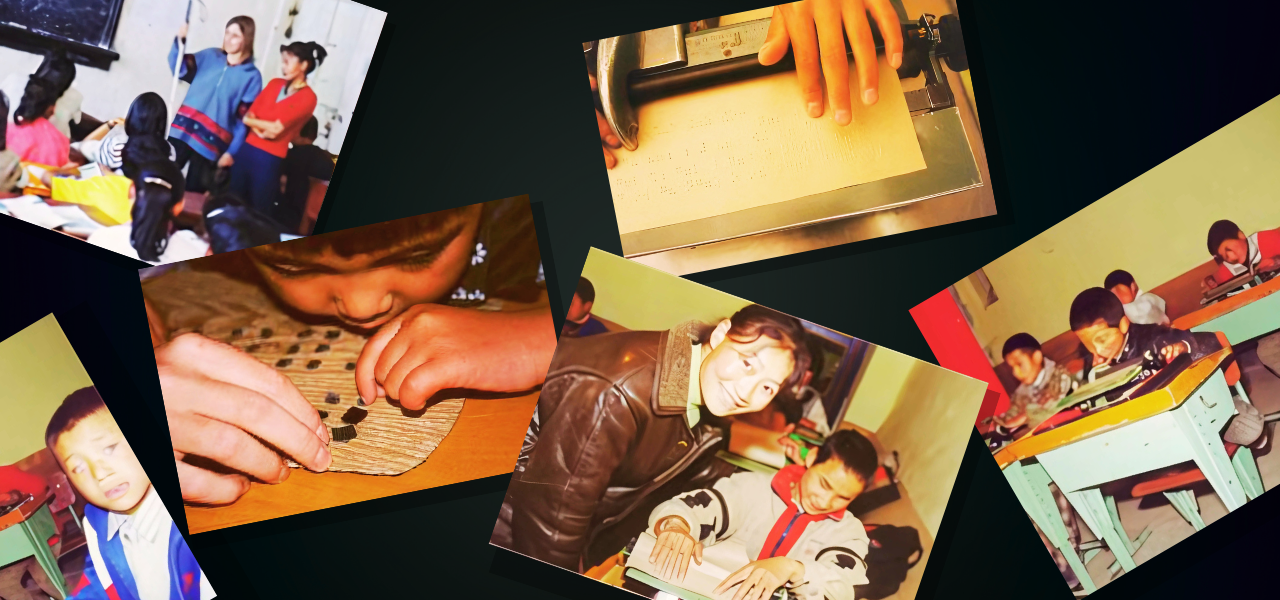

Sabriye and Paul started small. In 1998, in a country where blind children were hidden not only from strangers but even from their relatives, they opened a school and began enrolling children. Their friends provided the funding. The equipment was gathered from all over the world, from people who were moved by their seemingly crazy idea. By the time the school opened, Sabriye Tenberken had independently developed a Braille system for the Tibetan language and was teaching the children to read and write. Paul taught the children how to navigate their surroundings, recognize obstacles in their path, distinguish different sounds, and simply live in a world designed for the sighted.

The early success of the school in Tibet inspired its founders to establish Braille Without Borders. The name of the foundation, established by Sabriye Tenberken and Paul Kronenberg, was a reminder of Doctors Without Borders, whose work had become well known by the end of the 20th century. Braille Without Borders provided blind children in Tibet, and later beyond its borders, with resources to build confidence and autonomy.

The Braille Without Borders foundation quickly became a challenge to the way some societies treat those who are often labeled as “not like everyone else.” It questioned the mindset of a culture that prefers to “fix” those who are different rather than support them in gaining an education and a profession, tools that would help them navigate life in a world built for the sighted.

Neither Sabriye nor Paul ever tried to “fix” their students. Instead, they helped them — step by step — understand themselves, pursue their dreams, read books, and step outside into the world around them.

The Voice of a Child

When a child who has been hidden in the shadows since birth suddenly finds their voice and begins to believe in themselves, it signifies more than just the importance of education. It is almost a revolution. And Sabriye, more than anyone around her, understood that the dots of the Braille script are points of support for blind children in the modern world. Their voice finally becomes distinguishable among all the others.

One of the first students to join Sabriye and Paul’s school was a girl named Dolkar. Before coming to the school, she didn’t speak a single word — not because she couldn’t, but because hardly anyone ever spoke to her. Dolkar was blind, and in the village where she lived, that meant there was nothing to hope for. Within a year, she was reading, writing, and helping other children during lessons. And after three years, Dolkar was already teaching Tibetan Braille to the newcomers.

How do you work the land when you can’t see—but it’s your deepest dream? Is it possible to become a farmer like your father? For Tamdin, one of the school’s first students, that dream became reality. At the school, he not only learned to read and write, but also gained the practical skills he needed to become a farmer. Navigating the land, mastering agricultural tools, and working like a real farmer.

There were other students whose ambitions exceeded local expectations. One of them was Songtso, who moved to Europe and became an ambassador for the Braille Without Borders foundation. Blind from birth, Songtso shared his story with politicians, businesspeople, and educators at conferences with such confidence that his audience forgot about his blindness. He believed in himself and in the work he was doing for others, which helped him achieve great results as an ambassador.

The first graduates of Sabriye Tenberken and Paul Kronenberg’s school have grown up, and many of them give back to the place that helped shape them. Their success is not an anomaly or a miracle, but a vivid and living example that success goes hand in hand with belief, knowledge, and a will to live fully.

Braille Without Borders has shown that when blind children are given a chance to speak, they raise their voices — and the world listens.

Discover ways schools can support visually impaired students—check our blog.