Keratoconus: When the Cornea Loses Its Shape

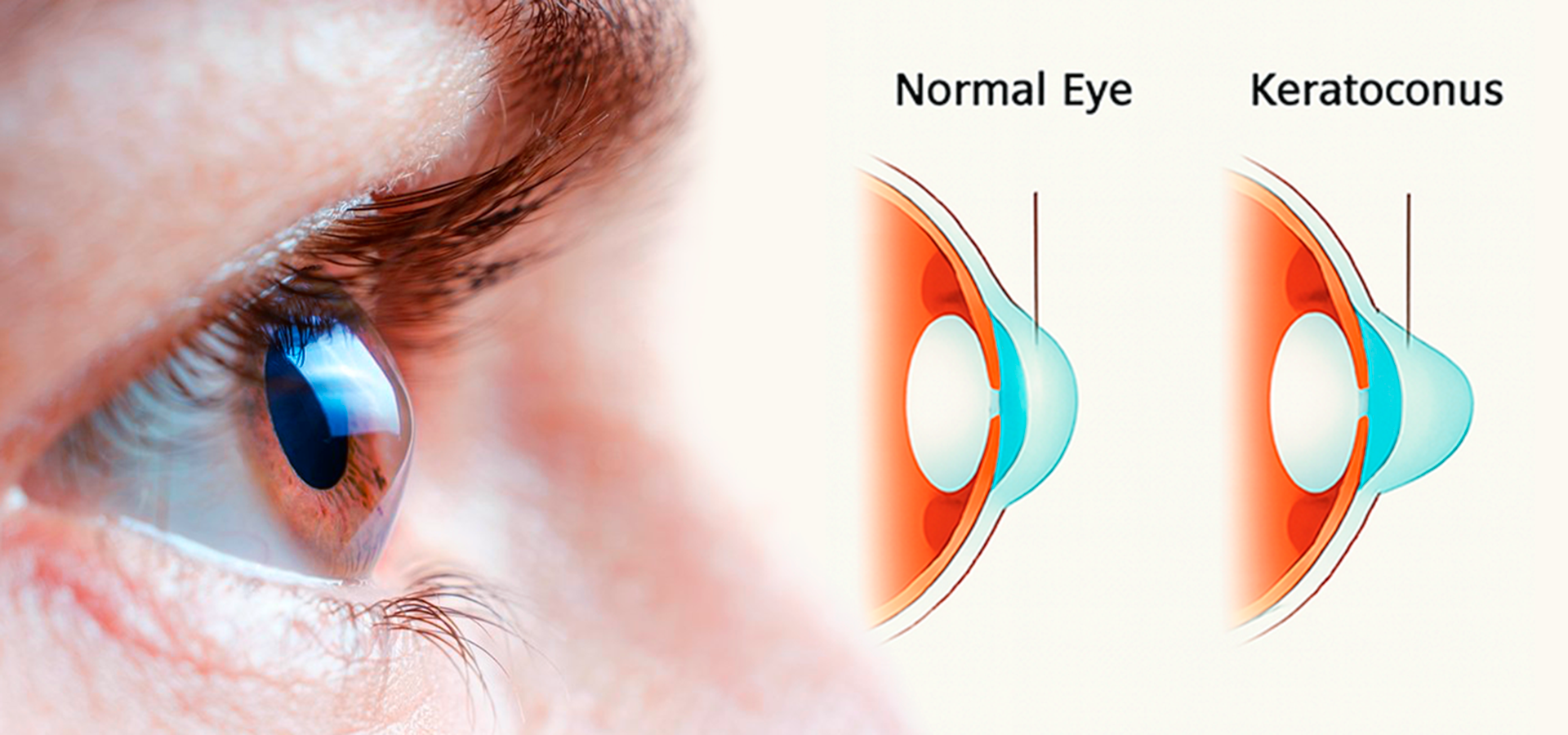

Keratoconus is a progressive eye disease in which the cornea (the transparent outer layer of the eye) gradually becomes thinner and deformed, taking on a cone-like shape. As a result, light rays passing through the altered cornea are refracted incorrectly, causing distorted vision: objects appear blurred, doubled, and surrounded by glare or halos, especially around light sources.

The disease usually develops slowly, over several years or even decades, and most often appears during adolescence or in the early twenties. Early diagnosis and modern treatment methods can effectively slow the progression of keratoconus and help maintain good vision quality for many years.

How to Recognize Keratoconus: Main Symptoms

In its early stages, the disease may be almost asymptomatic or mimic ordinary myopia (nearsightedness). However, over time, characteristic signs begin to appear:

- Blurred and distorted vision: straight lines begin to appear curved.

- Frequent changes in glasses or contact lenses: when vision worsens by 0.5-1.0 diopters or more within a few months, repeatedly.

- Double vision in one eye (monocular diplopia): even when the other eye is closed.

- Appearance of halos, glare, and light sensitivity, especially noticeable at night.

- Increased sensitivity to bright light.

- Eye fatigue and headaches, especially after reading or working at a computer.

If one eye begins to see worse than the other and vision continues to decline, it is important for the patient to describe all symptoms to the doctor in detail. And if the deterioration is rapid, they should insist on a full eye examination, not just a new prescription for glasses.

How Keratoconus Is Diagnosed

Diagnosis of keratoconus is performed by an ophthalmologist and takes little time. The patient undergoes a series of painless tests using specialized instruments that allow a detailed assessment of the cornea’s shape, thickness, and structure.

Modern ophthalmology offers advanced diagnostic technologies that can detect even the earliest signs of the disease.

- Corneal topography: a computer-based test that creates a three-dimensional map of corneal curvature. It is the primary method for early detection of keratoconus.

- Pachymetry: measurement of corneal thickness across its entire surface.

- Keratometry: determination of corneal curvature and refractive power.

- Slit-lamp examination: allows the doctor to observe characteristic structural changes in the cornea.

- Anterior segment tomography (OCT): helps assess corneal thinning and its internal layers.

Regular examinations are especially important for people with a family history of keratoconus or chronic allergies, as frequent eye rubbing is considered one of the risk factors.

Forms and Stages of Keratoconus

The progression of keratoconus is usually divided into several stages:

- Early (Stage I): minimal changes in corneal shape; vision can be easily corrected with glasses or soft lenses.

- Moderate (Stage II–III): the cornea becomes noticeably thinner and more curved, making vision harder to correct; rigid gas-permeable lenses are commonly used.

- Severe (Stage IV): significant corneal deformation and possible opacity; wearing lenses becomes difficult, and surgical treatment is required.

There is also an acute form of keratoconus (hydrops), a sudden rupture of the cornea’s inner layer. During this episode, fluid from the eye enters the cornea, causing swelling and a sharp loss of vision. This condition requires urgent medical attention.

How Common Is Keratoconus?

It was once believed that keratoconus was a rare disease, affecting about 1 in 2000 people. However, with improved diagnostic technologies, it became clear that the true prevalence is much higher from 1 in 400 to 1 in 500 especially in regions with hot climates and high ultraviolet radiation levels.

Keratoconus most often appears between the ages of 10 and 25 and can progress until around 35-40 years old, after which it usually stabilizes. Men and women are affected equally.

Modern Methods of Treating Keratoconus

Treatment is selected individually and depends on the stage of the disease.

- Glasses and soft contact lenses: effective at the earliest stages.

- Rigid gas-permeable lenses: help smooth the corneal surface and improve visual quality.

- Scleral and hybrid lenses: used for advanced corneal deformation, providing comfort and clear vision.

- Corneal collagen cross-linking (CXL): one of the most effective treatments. The doctor applies a riboflavin (vitamin B2) solution to the cornea and then exposes it to ultraviolet light. This strengthens the collagen fibers, making the cornea more rigid and preventing further thinning.

- Implantation of intrastromal ring segments (INTACS): small plastic arcs are inserted into the cornea to mechanically reshape its curvature.

- Corneal transplantation (keratoplasty): performed in severe cases when other treatments are no longer effective. Modern grafts usually heal well, significantly improving vision.

Can You Be Born with Keratoconus?

Keratoconus is not a congenital disease infants are not born with. However, genetic predisposition plays an important role. If parents or close relatives have had keratoconus, the risk of developing it is higher than average.

Risk factors include:

- Chronic allergies and the habit of rubbing the eyes.

- Down syndrome, Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, neurofibromatosis, and other inherited connective tissue disorders.

- Antioxidant deficiency and exposure to ultraviolet radiation.

Therefore, children in risk groups are advised to undergo an eye examination at least once a year.

Childhood with Keratoconus: How to Help a Child

For a child with keratoconus, both medical treatment and psychological support are crucial. The disease can affect school performance, self-esteem, and social interaction.

Parents should:

- Ensure the child does not rub their eyes, as this accelerates disease progression.

- Visit the ophthalmologist regularly and follow all recommendations for lens use.

- Explain that life with keratoconus can still be full and active. The child can attend school, play sports, and use a computer.

- If necessary, seek help from a school psychologist or ophthalmologist to assist with adaptation.

Thanks to modern medical technologies, most children diagnosed with keratoconus grow up with good vision and without significant limitations in daily life.