The Blind Man Who Saw Further Than Anyone — The Story of Sir John Fielding

People like John Fielding are often described as “the salt of the earth” — and rightly so. Born during the Age of Enlightenment (18th century) in England to a typical middle-class family of the time, Sir John became one of the founders of the urban police force in London.

Of Brothers and Sisters

At first glance, there seems to be nothing unusual in John Fielding’s biography of 18th-century England. A young man from a respectable family, with a half-brother and sister — Henry and Sarah — who were both notable writers, John tried his hand as a sailor and later became a devoted assistant to his half-brother Henry. His sister Sarah was a novelist who wrote only three books, but all of them gained great popularity. John’s brother Henry was not only a famous playwright but also a magistrate in London and someone deeply concerned with what was then called “the public good.”

The State of Safety

Safety has always been a cornerstone of civil life. But mid-18th-century London was an extremely dangerous place for the average citizen. Even during the day, ordinary Londoners didn’t feel safe, fearing not only deserted streets and alleys but also the paths in royal parks. Robberies and murders occurred so frequently that the policing system, rooted in the 17th century, eventually collapsed. Night watchmen and private guards couldn’t cope with the overwhelming number of petty and major criminals — not to mention murderers and rapists.

But what role did Henry and John Fielding play in bringing order to London, the largest city in 18th-century Europe? Why are they still remembered today? Why do the brothers — especially the younger, John Fielding — continue to serve as prototypes for detective fiction written by modern authors? To answer these not-so-difficult questions, we’ll have to start from the beginning.

Law and the Magistrate

John Fielding was born in 1721, but unfortunately, nothing is known about his childhood, his education, or where he studied. Some sources suggest he joined the Royal Navy, though there is no reliable evidence to confirm this. There are also no details about the circumstances under which 19-year-old John Fielding lost his sight; what is certain is that it happened after a failed surgical operation. As compensation for the surgeon’s negligence, Fielding received £500 — a significant amount for that time.

It is unclear how John Fielding used the £500, but what is certain is that his blindness did not stop him from studying law. Upon completing his legal education, he, like his elder brother Henry, became a magistrate in London. In the 18th century, a magistrate’s duties included combating crime, and this is exactly what the Fielding brothers dedicated themselves to.

Aftermath of War

Crime in London rose sharply after the signing of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, which marked the end of the War of the Austrian Succession. Since 1701, England had taken part in two bloody wars. The first was the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714), and although the Treaty of Utrecht brought relatively favorable outcomes for England, the country’s social and economic conditions remained poor.

A little over 25 years later, England entered another conflict — the War of the Austrian Succession — and the consequences of this war proved far worse than those of the War of the Spanish Succession. In the 18th century, the end of a war usually meant one thing: thousands of soldiers and sailors found themselves jobless and desperate, and many of them inevitably turned to crime.

A Reformer of Law and Order

The end of the war led not only to a surge in crime in London but also to the collapse of the existing security system, including the enforcement of laws, which was part of the magistrates’ responsibilities. The law enforcement system was overwhelmed and dysfunctional, relying heavily on night watchmen — elderly and unarmed individuals. Private security services were also largely ineffective and usually limited to protecting the property of those who could afford to hire them.

The Bounty Hunter Crisis

The institution of “bounty hunters,” created to capture criminals and bring them to justice, had lost credibility. Offenders often bought their way out of arrest. In many cases, bounty hunters would simply release criminals in exchange for money. There were even instances where the victims of crimes ended up being harassed by the very people meant to help them.

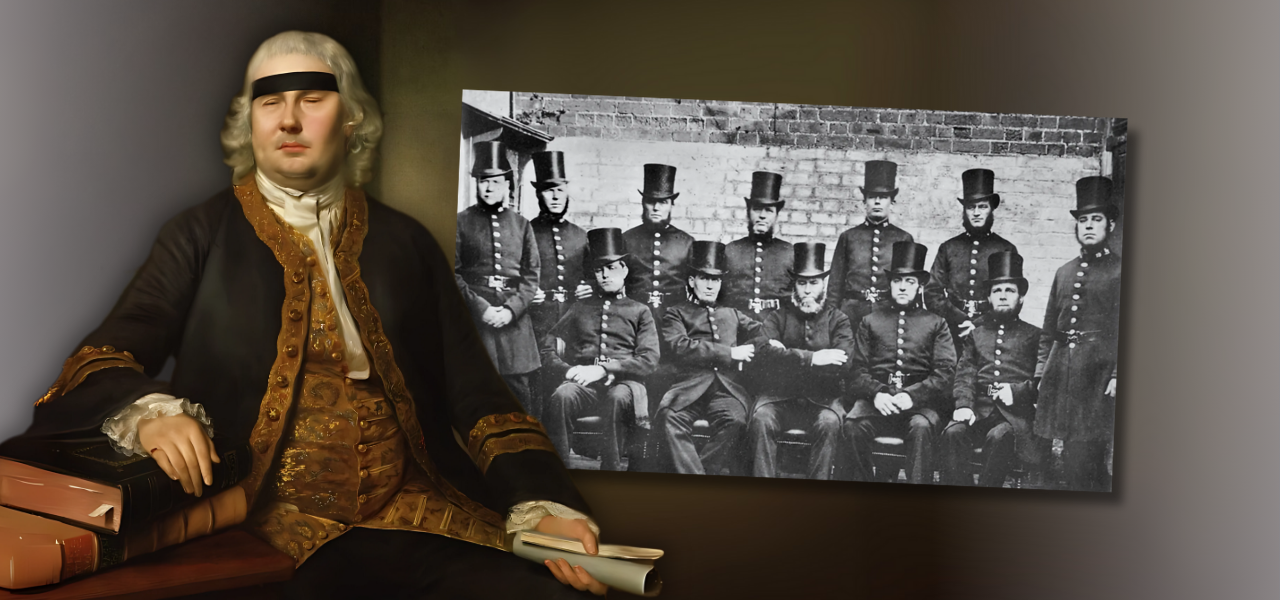

It was in this environment that Henry and John Fielding established England’s first voluntary police force, known as the Bow Street Runners. John Fielding served as Henry’s assistant and played a vital role in eliminating corruption among law enforcers and improving their professional standards.

Continuing the work of his brother Henry, who died in 1754, Sir John went on to found the Bow Street Horse Patrols in 1763. This mounted unit succeeded in tackling the rampant highway robbery plaguing the roads surrounding London.

Blind but Insightful

John Fielding was known for his sharp focus and stamina, and his contemporaries spoke of his unique abilities with awe. Despite being blind, Sir John had an extraordinary memory for voices and could distinguish one person from another purely by sound — a skill that made him an exceptional judge. He earned the nickname “Blind Beak of Bow Street” — “beak” being period slang for a magistrate — and the fact that he was not only a judge but a blind judge inspired deep respect.

He saw none of those he judged — and yet understood them better than most, the streets patrolled by his runners, or the roads watched by his horse patrol — yet he did everything in his power to make Londoners believe in justice and law. The story of Sir John Fielding is a testament to how a visually impaired man — or, as they said then, a blind magistrate—proved that while justice may be blind, it still hears and feels the people’s needs.

As Fielding himself once said: “I don’t need sight to tell an honest man from a scoundrel — I only need to hear how he speaks.” It’s hard to resist retelling one of the many anecdotes about Sir John:

One day, a street thief stood before him and tried to take advantage of the fact that the judge was blind, saying:

“I didn’t steal anything, sir! It’s a mistake.”

“Curious,” replied Fielding without lifting his head, “my hearing tells me you’re lying in the same voice you used yesterday while robbing the butcher in Covent Garden.”

John Fielding’s Legacy

History loves symbols, and John Fielding is one of them — even today.

A blind judge who learned to see the truth through layers of prejudice, bureaucratic negligence, and criminal apathy. He and his work have remained in the English collective memory for centuries. In the 19th century, John Fielding inspired the image of the just magistrate in the works of Charles Dickens. Echoes of Sir John’s traits can be found in Oliver Twist, Bleak House, and especially in Dickens’ essays on the London police. In Dickens’s eyes, Sir John was a principled enforcer of the law, walking the thin line between legal rigor and social justice. It may not be a direct portrait, but Fielding’s voice is unmistakably present in those texts.

American journalist and author Bruce Alexander wrote a series of historical detective novels featuring Sir John Fielding as the main character. In Blind Justice, Sir John is not just a magistrate but also a true detective: blind, yet guided by impeccable logic and an unerring instinct for justice. His portrayal in Alexander’s books resembles that of Sherlock Holmes — a Holmes of the 18th century, in a powdered wig and without a violin or Holmes’s darker habits.

Welsh writer Ken Follett took a different approach. Though Sir John does not appear in his historical novels, the world described in A Place Called Freedom is strikingly similar to the one Fielding lived and worked in — dusty courtrooms, debtor’s prisons, powdered judges delivering verdicts with no regard for context. This is the grim reality in which a blind magistrate like John Fielding fought to bring about change.

Even now, the voice of Sir John Fielding seems to echo through time — silent, listening, judging. And though he cannot see those present, he still discerns truth from falsehood.

Read our blog to uncover another inspiring story of Helen Keller, highlighting her incredible journey, accomplishments, and dedication to helping others.